About the Brightness Control

Of all the settings on the display, the brightness control is probably the most important. If brightness is set too low, the dark parts of the image are lost completely. If brightness is set too high, the image contrast goes down and the picture loses its “snap.”

We’re going to talk about how to set brightness correctly, but first we want to take some time to talk about some of the history and background of the brightness control. If you want to know why brightness needs adjustment, what’s really going on when you move the brightness control, and how different kinds of brightness adjustment patterns work, then read on. If you just want to know how to use your test pattern disc to adjust your brightness control, skip ahead to the section called “Using the PLUGE Pattern.”

History and Background

The name “brightness” is really not a very good one. Professional video engineers refer to “black level,” which is more descriptive. What you’re really setting is the input level that the display will consider absolute black. If the input is analog (such as component or VGA), then you’re setting a voltage level that the display will consider black. If the input is digital (such as DVI or HDMI), then you’re setting a digital value that will be considered black.

The reason it’s called “brightness” and not “black level” is that when you change the setting you’re not just moving the black level. When you move the brightness control up and down, you’re in effect sliding the range that your display will handle up and down. You move the black level up or down, and every other level as well. You’re adding or subtracting a constant amount from every brightness level on the display. So when you move the black level up by raising the brightness control, you’re also moving the white level (and every gray level) up at the same time. Once black level is set properly you can move the white level up and down without changing the black level by adjusting the “contrast” control, but we’ll save that for another article.

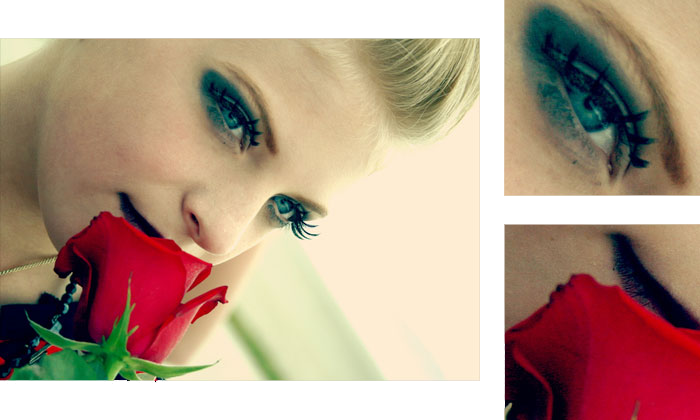

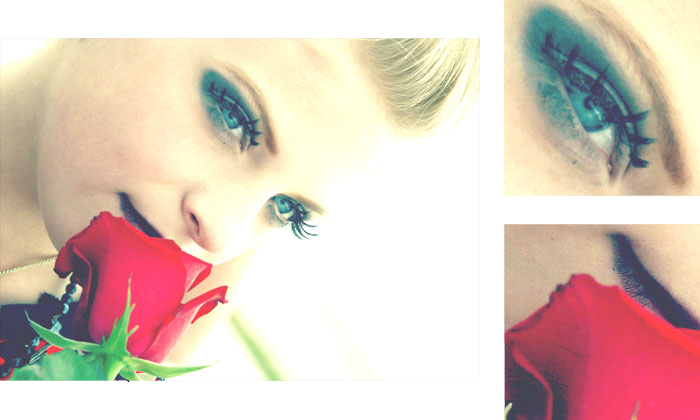

Brightness normal*

Brightness too low*

Brightness too high*

One question we get a lot is, “why does the brightness control need to be calibrated? Isn’t there a standard voltage or code value for black that can be locked in at the factory?” This isn’t a dumb question at all. Modern computer monitors almost never need brightness calibration, and a lot of LCD monitors either don’t have a control labeled “brightness” or have one that controls the backlight brightness, which is a completely different adjustment. Essentially modern computer monitors assume that the video card is going to produce a consistent signal that is exactly to spec. This is a pretty good assumption – in fact video cards do generally produce proper and consistent signals that are exactly (or very nearly exactly) to spec.

Unfortunately, video equipment doesn’t always produce proper and consistent signals that are exactly to spec, and even when they do television manufacturers don’t always ship the television set to expect the standard input levels. Television manufacturers want more than anything for their televisions to look different from (and better than) the other televisions at the electronics store. Setting the brightness control a little too low can improve contrast and “snap.” Setting it a little high can improve shadow detail, especially in a bright environment like a store. And sad to say, it’s not unheard-of for the manufacturer to just get the settings wrong. It’s getting better and better all the time, but it’s not quite to the point where you can feel confident that your television or player is absolutely correct.

The good news is that if you have a good test pattern, setting the brightness control is quick and easy. If your control isn’t set right you fix it, and if it’s already right you can find out instantly and move on with your calibration confident that you’re starting from a good foundation.

The key pattern for this adjustment is one called PLUGE. “PLUGE” is an acronym for Picture Line-Up GEnerator, which was the name of the piece of equipment used by early TV stations and broadcast studios to ensure their monitors were all set properly. That classic pattern is still in use, but on the Spears & Munsil disc the PLUGE patterns are a little different from the classic one. If you want to see a classic PLUGE pattern on the High Definition Benchmark disc, look at the SMPTE Color Bars 75% pattern – there’s a “classic” PLUGE in the lower right corner. Note that while the color bars was once the standard pattern for setting brightness (in SMPTE RP167), the current recommendation is to set brightness using a larger pattern like the PLUGE Grayscale pattern on the Spears & Munsil disc.

Classic PLUGE (with brightness turned up)

Let’s talk about the classic pattern first before introducing the Spears & Munsil version. The classic PLUGE pattern consists of a background that is set at the standard reference black level, with two rectangles on it. One rectangle is set slightly higher than the reference black level and the other is set slightly lower than the reference black level.

This may be a new concept, and it bears repeating: one of the rectangles is set at a level lower than the reference black level. This is possible with video signals, because video allows for levels below reference black. In digital video with 8-bit values, reference black is at 16, so all the levels from 1-15 are “below black.” (0 and 255 aren’t used in digital video for picture information – they’re used as special signaling codes.) The reasons for this situation are historical. Digital video encoding was designed for converting an analog signal in a wire into a stream of digital information, and video engineers were acutely aware that the signal in the wire wasn’t always perfectly adjusted. The signal might have been broadcast across the country and passed through several different pieces of video gear each with constant variations as a result of heat, age, and so forth. Allowing a certain amount of leeway in the encoding range seemed like a prudent thing to do. If the voltage went down somewhere along the line, black might end up encoded at level 5, say. Because video technicians tended to encode a PLUGE signal at the beginning of every transmission and recording, matching the black level of the transmission or tape to the levels of the local equipment was easy.

These days video equipment is built to tighter tolerances and much more of the broadcast chain from the network to the home is transmitted and stored digitally. Nowadays the below-reference values in the video signal are mostly used for the PLUGE pattern, and to a limited extent to allow for some wiggle room in the processing circuitry of displays and players. For this reason, some players and/or displays don’t bother transmitting or displaying the values in the digital signal below 16. This isn’t a good idea, if nothing else because it makes it harder to set the black level properly. It can also make a very subtle difference in the shadow detail, because in practice the value of one pixel can affect the pixels next to it, especially when the image is scaled up or down. You can find out if you have one of these players or displays that doesn’t pass the below-reference signals by putting up a PLUGE pattern and turning the brightness way up. If the darker bar won’t appear no matter what, your player or display isn’t passing the below-reference signals. Not to worry, you can still set brightness. It’s just a little trickier. Read on.

Classic PLUGE (below-black unavailable)

On the Spears & Munsil High Definition Benchmark disc, the standard PLUGE pattern (called “Brightness” in the Video Calibration section, or “PLUGE Grayscale” in the Advanced Video->Setup section) has some useful additional features. First of all, on the classic pattern the left bar is 4% below black and the right bar is 4% above black, which is a fairly large range. There are a lot of settings in that range that will still look correct. So we added two more bars at 2% below and 2% above black. These give you a tighter range of adjustment, but to see them clearly you’ll need to be a dark room with your eyes adjusted to the light.

Spears & Munsil PLUGE Grayscale (brightness raised)

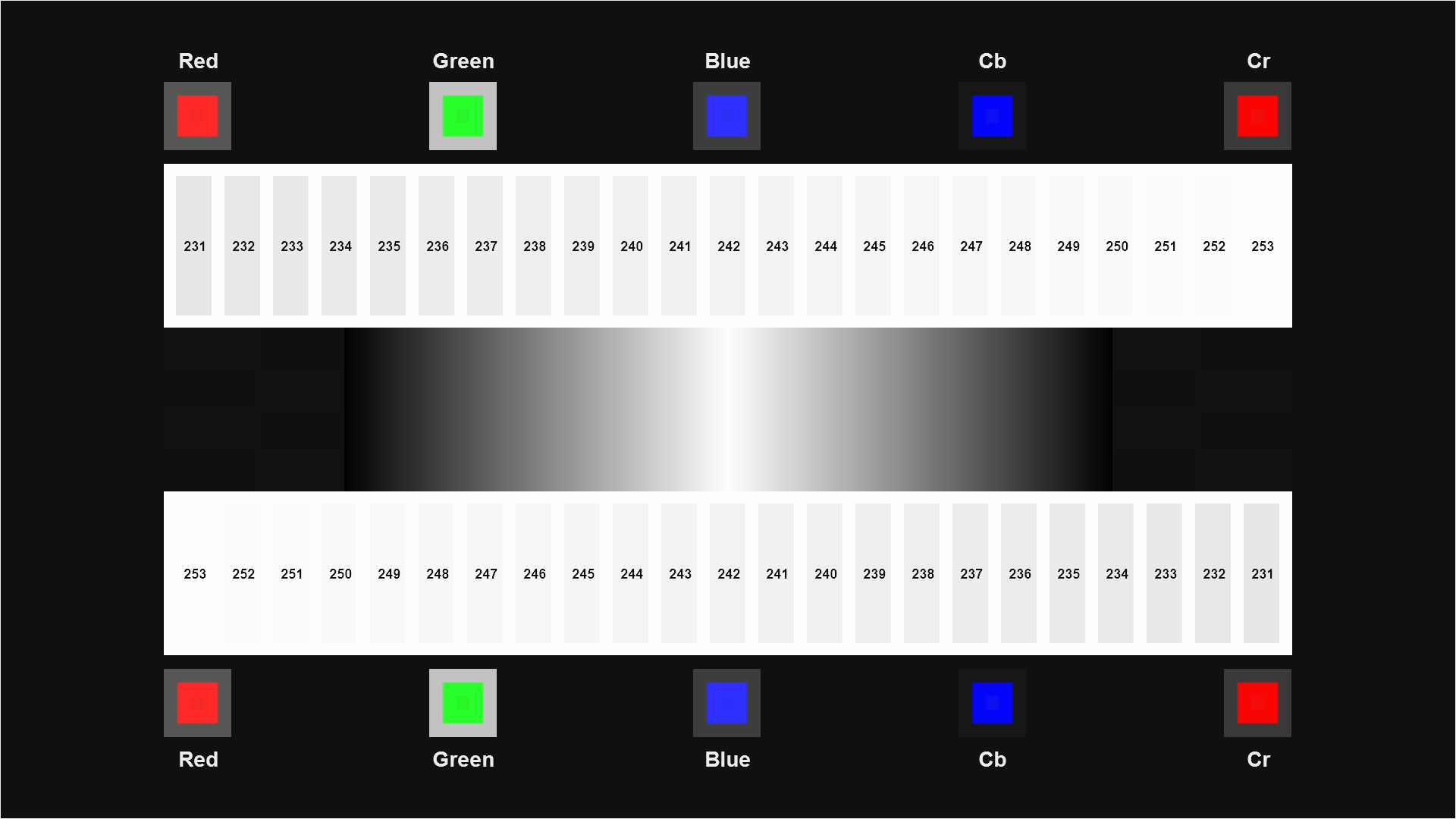

Secondly, there is a very faint checkerboard pattern in the background of the Spears & Munsil PLUGE that is alternating between blocks at 16 (reference black) and 17 (1 above reference). This is handy for those with DLP displays. See “Using the PLUGE Pattern,” below, for how to use the checkerboard properly.

Spears & Munsil PLUGE Grayscale (checkerboard brightened)

The PLUGE Grayscale pattern also has four rectangles around the edge of the screen, which are there to raise the overall energy level of the pattern to be closer to a real-world image. When the PLUGE pattern is on a completely black background, the screen is very close to complete black, which isn’t representative of real-world dark scenes. Most dark scenes in movies have some bright objects here and there.

In addition to the PLUGE Grayscale pattern, there are also PLUGE 0% and PLUGE 15% patterns. PLUGE 0% is on a completely black background, and PLUGE 15% has a gray border around the screen. These can be used to check whether your display is holding the black level properly when the screen is near complete black, or when there is something brighter on the screen. They’re not used to set the brightness control, as a general rule. You can look at them after setting the brightness control and you should see the right bars but not the left bars. If you don’t see the faintest right bar on PLUGE 15%, then you’re missing some shadow details when the rest of the image is bright. In that case you might want to “fudge” the brightness control up a notch or so to split the difference between the perfect settings for a dark image and a bright image. And if you can see the left bars on PLUGE 0%, that means your black level isn’t absolutely at the minimum level your screen can reproduce, but our recommendation in that case is to leave it that way, since the PLUGE Grayscale is a better match to the kinds of dark material you’ll actually be watching.

Spears & Munsil PLUGE 0% (brightness raised)

Spears & Munsil PLUGE 15% (brightness raised)

Using the PLUGE Pattern

Spears & Munsil PLUGE Grayscale Pattern (Called “Brightness” in the Video Calibration menu)

This has four main bars: -4%,-2%, +2%, and +4%, from left to right. To use this pattern properly, you need to be in a dark room with your eyes fully adjusted to the ambient light level. Turn on the display and turn off the lights, and allow a few minutes for your eyes to adjust. If you don’t want to use the 2% bars (or aren’t in a dark room), just use the 4% bars on the outside and follow the instructions given below for the Classic PLUGE Pattern.

The two left bars are below reference black and the two right bars are above reference black. If you are using a display and player that can pass the below-black signal, you just raise the brightness control until all four bars are visible, then lower it again until the two left bars disappear but the two right bars are still visible. If your controls are too coarse and you can’t keep the faintest right-hand bar visible while making the faintest left-hand bar invisible, err on the side of keeping both right-hand bars visible.

If you’re using a display that can’t pass below-black (you’ll know because you won’t see the two left bars even with the brightness turned way up), then start by raising the brightness if needed so you can see both right-hand bars. Lower the brightness control until the faintest right bar disappears, then raise it a notch or two until both right bars are visible. When everything is set right, the far-right bar should be clearly visible, and the darker bar should be just barely visible above the background level.

Spears & Munsil PLUGE Grayscale (brightness too high)

Spears & Munsil PLUGE Grayscale (brightness too low)

Spears & Munsil PLUGE Grayscale (correctly adjusted)

If your eyes are fully adjusted, you will probably be able to see the very faint checkerboard in the background of the pattern with the brightness turned up. This was designed for DLP displays. On a DLP, you can get close to the screen and see the difference between the 16 and 17 clearly when the brightness is perfect, as the 17-level blocks will have moving digital “noise” caused by the DLP temporal dithering, while the 16-level blocks will be completely black and motionless. If there is no brightness setting on your DLP where there is motion in the bright squares on the checkerboard but no motion in the darker squares, then keep the setting that has motion in all the squares; if you make the background jet black you’ll be cutting off picture information, and in general it’s better to have the brightness a notch too high than a notch too low.

Classic PLUGE Pattern (Lower-Right Corner of Color Bars 75% on Spears & Munsil HD Benchmark)

The left bar is below reference black and the right bar is above reference black. If you are using a display and player that can pass the below-black signal, you just raise the brightness control until both bars are visible, then lower it again just until the left bar disappears. The right bar should be clearly visible at the end, and the left bar completely invisible.

If you’re using a display that can’t pass below-black (you’ll know because you won’t see the left bar even with the brightness turned way up), then lower the brightness control until the right bar disappears, then raise it a couple notches or so until the right bar is clearly visible.

Classic PLUGE (brightness too high)

Classic PLUGE (brightness too low)

Classic PLUGE (correctly adjusted)

Conclusion

In the end, it’s a very simple operation. Once you know what to do you can calibrate brightness in about 30 seconds – perhaps longer if you really want to get everything just perfect.

Next up: Setting Color and Tint.

*Photo by D Sharon Pruitt used under Creative Commons license.